About a month ago, I started watching Ken Burns’ documentary on the National Parks. And what I saw surprised me: China. Continue reading “China, reflected in Ken Burns’ “National Parks” documentary”

Of China’s Countryside Bachelors, and One Chinese Man’s Divorce

Er Ge, my second-oldest brother-in-law, wanted to marry for life.

His bride in 2005 was a lovely, lithe girl of 18 from Guizhou who worked in a local sewing factory, often evenings. I never forgot her almost ubiquitous smile in my presence. It was inscrutable, a smile that remained far too long to be just about happiness.

Mysterious smile or not, she must have made Er Ge happy, or at least relieved.

For years, his mother had fretted over finding him a wife — not easy, given the distorted sex ratio, especially in the countryside. Er Ge’s own personality added challenges. He was always the wallflower of the family, parsimonious with his own words, as if they were a precious currency. It took years before I even held a bona-fide conversation with him. But Er Ge’s mother didn’t want him to take years before he understood romance. So, following in a long tradition of mothers who arranged marital affairs for their sons, she made inquiries in town, and eventually found him a bride. He would be the last of the three brothers to be matched.

Er Ge is a peasant, and still resides in his family home, so they held the celebration at home too. He donned a black polyester suit and tie; she dressed in a white Western-style tulle wedding gown with roses in her flowing black hair.

She may have looked like a fairytale bride, but there is no fairytale ending here. Continue reading “Of China’s Countryside Bachelors, and One Chinese Man’s Divorce”

China’s ‘Little Emperors’: Children in country tend to be indulged by families

This is the concluding article in a four-part series of articles providing a snapshot of modern life in China in observance of October 1, 2009, the 60th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China. It was published October 11, 2009 in the Insight section of the Idaho State Journal

————

It was Chinese New Year 2003 when I first met Yu Kaiqi, the boy who would become my nephew. Almost a year old, he was bundled up in endless layers, like a silkworm cocoon — and just as precious to my future father-in-law, Yu Huimin, 61, who carried him everywhere. I was stunned. If this boy were in the US, his parents and grandparents would have been letting him teeter and totter on the floor, taking his first steps to explore the world. But not here. For almost the entire day, he was tucked safely away in his doting grandfather’s arms.

Today, Yu Kaiqi, now seven years old, is still the family’s center of attention — but for all the wrong reasons. Throwing objects at the teacher. Lying. Sassing his parents. Daily temper tantrums. Not going to bed on time.

Unfortunately, Yu Kaiqi is no anomaly in China. Some studies, including a 2006 paper from Jinan University, suggest that 11 percent of young Chinese children misbehave. Others, including a 2002 Qingdao University paper, put the figure at 23 percent. Suppose you apply that lowest estimate — 11 percent — to the 2000 China census count of 95 million two- to seven-year-olds. That adds up to as many as 10 million Chinese children troubling their families.

And when they’re vexed by a naughty child, families look for explanations. Jin Genxiu, my 55-year-old mother-in-law, believes Yu Kaiqi’s bad temperament is the cause. Yu Huimin blames the school environment and declining standards in society. But there’s a culprit more close to home: parenting. Continue reading “China’s ‘Little Emperors’: Children in country tend to be indulged by families”

For China’s Youth, Money Often Trumps Love in Marriage

This is the third in a four-part series of articles providing a snapshot of modern life in China in observance of October 1, 2009, the 60th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China. It was published October 4, 2009 in the Insight section of the Idaho State Journal.

——-

Anya Wang, a 36-year-old human resources professional, used to believe in a loving marriage until earlier this summer. Just when she and her fiancee were going to get married within a month or so, he left her — for a woman with more money. “I once wanted to marry for love,” she admitted. “But I’m changing my ideas. Maybe I will simply marry for personal benefit.”

Wang is not alone. Caroline Jin, a 33-year-old translator, voiced a similar change of heart during a recent conversation about dating and marriage. “Before, I didn’t care about whether my future husband had money and a home,” she explained. “But now, I think I would expect those things.” She giggled with her hand covering her mouth, as if embarrassed to admit the truth.

Jin and Wang are changing the way they look at marriage. For them, and many others in China, money has increasingly edged out love in marriage decisions. Continue reading “For China’s Youth, Money Often Trumps Love in Marriage”

One Naxi Artisan in China’s Vanishing Culture in Lijiang

This is the second in a four-part series of articles providing a snapshot of modern life in China in observance of October 1, 2009, the 60th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China. It was published September 27, 2009 in the Insight section of the Idaho State Journal.

———-

Lijiang, Yunnan Province, China — At the foot of the sacred Jade Dragon Snow Mountain, a peak soaring to over 18,000 feet in a mountain range just shy of the Tibetan border, I found my first moment of true serenity after weeks of traversing across China.

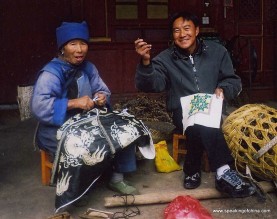

I was staying in an old wooden Chinese-style courtyard house, one of the many traditional homes lining a cobblestone street in Baisha, Lijiang that offered a rare glimpse into the life of one of China’s most distinctive ethnic minorities: the Naxi people. Baisha was once the capital of the ancient Naxi Dongba Kingdom, and even today the place seems to exist in another era. I saw Naxi women dressed in their characteristic blue blouses and pants wrapped with a blue or black apron, roaming the streets with baskets on their backs filled with produce, or babies tucked gently into a brightly colored child holder. Every now and then a herd of cattle or goats, often led by a man wearing the traditional cowboy-like Naxi hat, would flood the entire street, the soft click-clacking of their hooves the rhythmic accompaniment to this animal parade.

I am also here for something else — my friend Bi Zhihui, a 37-year-old artisan who is Naxi and Yi, one of China’s other ethnic minority groups. Continue reading “One Naxi Artisan in China’s Vanishing Culture in Lijiang”

For Many of China’s Rural Residents, Health Insurance is Not Enough

This is the first in a four-part series of articles providing a snapshot of modern life in China ahead of October 1, 2009, the 60th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China. It was published September 20, 2009 in the Insight section of the Idaho State Journal.

————

Zhongshan, Tonglu County, Zhejiang, China — In a old wooden home hidden behind Zhongshan’s main street is a place where Ye Xianna, my husband’s 76-year-old grandmother, is quietly putting her trust in Jesus — to protect her against illness.

After sitting with for nearly four hours in the rows of turquoise-colored pews that felt like tiny park benches — witnessing speaking in tongues, singing hymns in Chinese, and preaching on the virtues of Christianity — it was one of the congregation who spoke the most important reason why Ye, like many others in the church, was present that morning.

A senior man in a tan-striped polo shirt and oversized brown pants, with squinty eyes, stubble and a mostly toothless smile, stepped behind the turquoise podium with a blood-red plastic cross attached to it, and began addressing the room.

He was speaking in the local dialect of Tonglu — one of the thousands of dialects in China that sounds different from the country’s official Mandarin Chinese — so I couldn’t understand his words, at first. “What is he saying?” I asked Ye, sitting next to me in the pew in a flowered blouse and pants, with her wiry, shoulder-length gray hair tied into two pigtails.

Ye, whose local dialect is better than her Mandarin Chinese, explained it to me as simply as she could: “His arm used to hurt. Then he believed in Jesus, and it stopped hurting.”

Her simple words spoke a powerful idea: that Jesus heals, literally.

And for many churchgoing senior citizens in China’s countryside, like Ye, it’s the one thing they can count on in the face of a rural healthcare system that is still far from ideal. Continue reading “For Many of China’s Rural Residents, Health Insurance is Not Enough”

The Troubling Chinese Mother-in-law Relationship

It could have been any other pile of clothing — pastel linen blouses, jeans with a flower pattern embroidered on the side, a silk robe in peacock blue, and more. But they were my the clothes of my sister-in-law, Da Sao, married to my husband’s eldest brother. And my Chinese mother-in-law was anxious to clear them away.

It could have been any other pile of clothing — pastel linen blouses, jeans with a flower pattern embroidered on the side, a silk robe in peacock blue, and more. But they were my the clothes of my sister-in-law, Da Sao, married to my husband’s eldest brother. And my Chinese mother-in-law was anxious to clear them away.

“Look at all of these clothes,” she said, lifting up a shirt and then the jeans, sighing. “She buys them on a whim, wears them once, and then brings them over here — and never wears them again.” Then, smiling towards me, she added, “you should wear them.”

It was a lonely pile of clothes, desperate to be worn. But I couldn’t shake the feeling that this was more than just housekeeping — because Da Sao was becoming infamous during our dinnertime conversations.

One day, my inlaws chastised Da Sao for enrolling her son, Kaiqi, in too many afterschool activities. Another day, they declared her too lazy, spending too much time on the computer. On another, they decided her cooking wasn’t up to snuff. I couldn’t help but notice that, even as both in-laws spoke, my Chinese mother-in-law supported the brunt of these indictments.

Da Sao is no saint — but not once did my inlaws suggest that Da Ge, her husband, did anything wrong (Da Ge, according to my husband John, is an uninvolved father who has also exacerbated his son’s behavior problems). Clearly, this was a troubling Chinese mother-in-law, daughter-in-law relationship.

But it’s not just Da Sao. For thousands of years, daughters-in-law have dreaded their Chinese mothers-in-law. Why? Continue reading “The Troubling Chinese Mother-in-law Relationship”

Saying “I love you” with a toilet: of indirect displays of love in Chinese families

Nobody really asked why that toilet was built before Chinese New Year 2003 — at what would later become my in-laws home. They had always lived without indoor plumbing, instead using a feitong (a large urnlike container) or, for the room, a matong (a small bucket with a top). The feitong and matong made it easy to recycle human waste on their fields, and the whole system had worked just fine.

But then again, they had never hosted a foreign girl (me!) until that Chinese New Year.

That toilet is like many things in Chinese culture, where “I love you” is an unspoken phrase that finds its voice in the sumptuous feasts that fill the dinner table, the hongbao stuffed with crisp, red RMB bills, the boxes of green tea and smoked tofu that friends and relatives forcibly stuff into every last empty corner of your luggage.

My in-laws do not hug or kiss me, or any of their children. But they, like many Chinese, find extraordinary, indirect ways of saying they care. Continue reading “Saying “I love you” with a toilet: of indirect displays of love in Chinese families”

On the Rarity of Foreign Women and Chinese Boyfriends/Chinese Husbands

When I’m in China, I tend to turn a lot of heads, especially in the countryside — and that’s not just because I’m a foreigner. It’s because I’m often seen holding hands with my Chinese husband.

It’s true — the sight of a foreign woman and Chinese boyfriend or Chinese husband is much rarer than its counterpart, the foreign man and Chinese woman.

If you go to any major city in China, you will invariably run into the foreign man-Chinese woman pairings in any major tourist or shopping destination; not so with foreign women and Chinese men. It’s easy to gauge this reality on the website Candle for Love (CFL), devoted to helping US Americans bring their loved ones over from China. CFL is like a tidal wave of American men in love with Chinese women, with only a rare American woman/Chinese husband surfacing to break the monotony. Continue reading “On the Rarity of Foreign Women and Chinese Boyfriends/Chinese Husbands”

The sensitive foreigner’s guide to staying healthy in China

Forward: I wrote this article many years ago, but was reminded of it by my recent trip to China, where I caught the flu twice — including having the interesting experience of getting in-home IV service. After all of these years, I am still a sensitive girl when it comes to getting ill in China. If you are too, you’ll enjoy this classic piece.

——–

Have you ever had such a severe case of the flu that it took away your voice? Have you experienced months of annoyingly frequent respiratory infections? Did you ever have cases of…er…diarrhea so horrible that you had to leave the room mid-sentence? Do you yearn for the days in your home country, when you only got ill once or twice a year?

If you’re a foreigner in China, you just might understand this. Getting up close and personal with a lot of odd colds, flus, and…yes, diarrhea…is all part and parcel of committing yourself to living in China.

But, for some of us foreigners, China’s illnesses have a wrathful hold. Look into our gentle, tired eyes, and you’ll see the tell-tale signs of multitudinous trips to hospitals, pharmacies, and practitioners of traditional Chinese medicine. Look in our homes, and you’ll find several Chinese traditional remedies hiding in the refrigerator, and boxes of prepared cold medicines strewn about the sitting room.

However, I discovered that surviving China’s illnesses goes beyond mere medicines, treatments, or therapy. Surviving demands that you take a holistic approach to your body and lifestyle.

With this “holisticâ€, common sense approach in mind, I’ll share what I’ve learned from my experiences, plus all of that good motherly advice from my Chinese friends. [see disclaimer at bottom] Continue reading “The sensitive foreigner’s guide to staying healthy in China”