Ask foreigners in China what they do for a living, and chances are you’ll hear a common answer – teaching English.

I’ve done it before. Most of my friends here have too. In fact, it’s such a prevalent gig for foreigners in China that you might even call it a rite of passage.

But anyone who has taught English in China also knows there’s a dark side to the profession.

During my first year teaching in China, this one white American guy who had signed on to work for our program never showed up and placed us all in jeopardy. (I later discovered he was a hard-core alcoholic.)

Later in Hangzhou, I bumped into a white American guy on a Hangzhou bus who confessed his secret for getting English teaching jobs – lying about his credentials. He smirked about how he had hoodwinked schools in China into believing he actually had a college degree, even though he was only a high school graduate.

Egads.

It’s hard to believe that I could actually inhabit the same profession as those two guys. But it happens, more than we’d like to talk about.

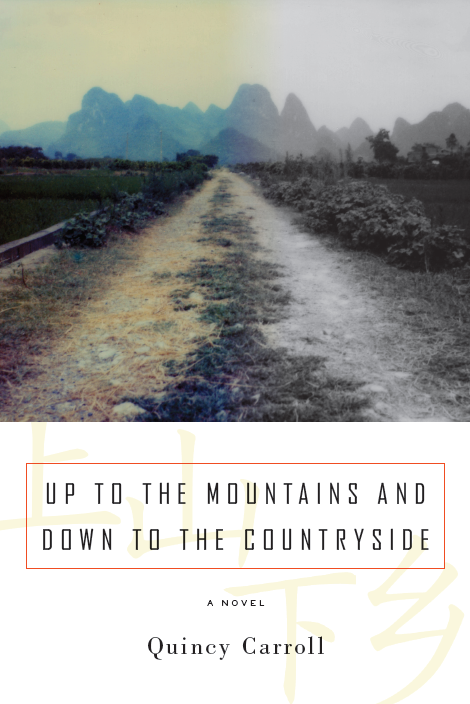

For writer Quincy Carroll, this is the stuff of a great novel. In this case, his new novel Up to the Mountains and Down to the Countryside.

Set in the rural town of Ningyuan, Hunan Province (where Carroll himself actually taught English as a volunteer), the story centers on the clash between two white Americans — deadbeat Thomas Guillard and the idealistic Daniel – and the young Chinese student who gets caught between them. Up to the Mountains and Down to the Countryside is a thoughtful look into the experience of being a foreigner in China, as well as the good, bad and the ugly of teaching English.

Set in the rural town of Ningyuan, Hunan Province (where Carroll himself actually taught English as a volunteer), the story centers on the clash between two white Americans — deadbeat Thomas Guillard and the idealistic Daniel – and the young Chinese student who gets caught between them. Up to the Mountains and Down to the Countryside is a thoughtful look into the experience of being a foreigner in China, as well as the good, bad and the ugly of teaching English.

It’s my great pleasure to introduce you to Quincy Carroll and his new novel Up to the Mountains and Down to the Countryside through this interview.

Here’s Quincy’s bio from Goodreads:

Here’s Quincy’s bio from Goodreads:

Quincy Carroll is a writer from Boston, Massachusetts. After graduating from Yale in 2007, he lived in China for three years, where he taught English and worked as a copywriter. He currently teaches Mandarin in Oakland, California. His debut novel, Up to the Mountains and Down to the Countryside, was published in November 2015 by Inkshares.

You can learn more about Quincy and his new novel at his website. Up to the Mountains and Down to the Countryside is available on Amazon.com, where your purchase helps support this site.

As a bonus, Quincy has an original song from the novel that you can hear at Soundcloud. (It’s the song Daniel performs in Chapter 12 for his students at the English competition in the school gymnasium.)

—–

What drove you to write this novel?

I arrived in China with quite a bit of uncertainty; I’d just quit my job in finance, and I was looking for direction. I didn’t know how to define myself. One of the first things I noticed was that there were a lot of other expats in the same boat—people of all backgrounds and ages, looking for some type of purpose. What I found most interesting, however, were the different ways in which people handled said uncertainty. For the most part, the volunteers in my cohort (I served through a program named WorldTeach) were gracious and curious when it came to interacting with people from another culture, but there was another group of foreigners (Westerners, especially) that seemed to view everything in China as beneath them.

That was really what spurred me to begin brainstorming a plot for the novel. I understand that Up to the Mountains and Down to the Countryside is far from the first story to examine the questionable influence of Westerners in Asia, but given the massive influx of foreigners in China over the past several decades, I believe it’s a timely, important tale worth retelling.

How did you conceive of Guillard?

Again, I was astounded by the number of “arrogant, lewd and racist” people I met when I touched down in China. Similarly to other characters in the book, Guillard is an amalgam of numerous expats I had encounters with over the course of my time abroad. I have been surprised since the novel’s release by how many readers have written to ask if I based the character on so-and-so from such-and-such a province, most of whom I’ve never met and most of which places I’ve never even been to before. Just goes to show how prevalent the archetype is.

I’ve also had many people ask me whether all Westerners in China are “that bad.” I’d like to state that I met some of the most thoughtful, kind people while abroad. I hope the story avoids coming off as an indictment—it’s more of a critique.

How did you conceive of Daniel?

I’ll just say it to get it out of the way: Daniel is the most autobiographical character in the book, although I’m sure that surprises no one. His struggles with questions of identity and purpose were written as a form of catharsis, but I took inspiration from additional sources as well (both literary and personal). I like to think that there is a bit of John Grady Cole in him, but that’s probably an overestimation of my writing. Fellow volunteers from the WT China program will probably be able to pick out aspects of Daniel’s personality that were drawn from their own or those of others we knew. In the end, a writer’s primary source of inspiration is almost always direct experience—what’s fun is that you get to play with the details you’re given and turn disorder into art.

One example of this in Up to the Mountains and Down to the Countryside is Daniel’s appearance: long, dyed hair, sleeve tattoos and gauged ears. Now, as far as I can remember, I didn’t meet anyone who looked like that in China, but just like Guillard’s deformities, I chose to give him these characteristics to add an external layer to his personality: in this case, a young man who has gone off the beaten path and is desperately trying to stand out. Another reason I think this worked is that, as a foreigner in China, you’re constantly under the attention of others. I was trying to capture some of this in Daniel’s outlandish physical appearance, but maybe it was just hyperbole, more than anything else.

What are some of the greatest challenges of teaching English in China?

I held two very different positions when I was in China that I believe are common among expats. Both are touched upon in Up to the Mountains and Down to the Countryside. As I’ve already mentioned, I volunteered in the Chinese countryside for two years via a Western NGO. Resources were scant, enthusiasm among our students was mixed, and aside from a modest stipend we received each month, payment was non-existent. For me, one of the biggest challenges was maintaining a sense of commitment throughout the year when it felt like we were there more because we were foreigners than because we were dedicated teachers. I certainly took the job seriously, but at times I wondered if anybody—my students, the administration, fellow teachers—cared about what I was doing. I collected grades my first semester in town, for example, only to find out that they were never included on my students’ report cards.

When I lived in Changsha, the provincial capital, several years later, I tutored high-school students from affluent families who were willing to pay through the roof for an American teacher. Since I had graduated from Yale, rates were even higher than expected, and even though I came prepared to each lesson, it was hard not feeling at least a little extortionary. Once again, my status as a foreigner made me uncomfortable, but I was in need of money and trying to support myself as a writer, so I didn’t say anything.

During the second half of that year, I started working for a local consumer tech company, and in addition to my copywriting duties, I ran a class in Business English every Monday. That was undoubtedly the most satisfying teaching experience I had in the country, as my colleagues genuinely wanted to learn. Most of them were in customer service, so they had to use the language every day.

What do you want people to come away with after reading the book?

More than anything, I hope that readers come away from the novel with a greater sense of humility and the ability to see themselves as part of a larger, globalized world. In addition to that, I hope the story makes them feel somewhat uncertain of who they are. I know that probably sounds a bit strange, but I’m a staunch believer that many of the greatest evils in our world result from one thing: an overinflated sense of self-importance. As the U.S. and China continue to challenge each other on the world stage, I hope that stories like Up to the Mountains and Down to the Countryside continue to remind us that we’re all lost in this together.

—–

Thanks so much to Quincy Carroll for this interview! You can learn more about Quincy and his new novel at his website. Up to the Mountains and Down to the Countryside is available on Amazon.com, where your purchase helps support this site.

As a bonus, Quincy has an original song from the novel that you can hear at Soundcloud. (It’s the song Daniel performs in Chapter 12 for his students at the English competition in the school gymnasium.)

I know I probably won’t be the first to say this, but what Quincy Carroll has said really touched a nerve with me. I worked as a teacher in China for 2 years (also in Hunan province!) and, like Carroll, I met with the same kind of unsavoury characters.

I’m so glad that someone sane and unprejudiced is finally voicing the opinions that we’ve all been thinking! Too often I came across foreigners who would get angry if people didn’t speak English, too often I met men well into their 50s and 60s looking to find 20-year-old Chinese girlfirends, too often I experienced the shocking level of vitriol poured onto Chinese people simply for cultural differences. It made me so angry!

I shall definitely be picking up a copy of “Up to the Mountains and Down to the Countryside” when my paycheck comes through this month!

That means so much to me, Madison. Thanks for your support! I hope that the book delivers on its promise and resonates with your own experience of teaching in China.

I have no idea why a white guy has to lie to get an English teaching job in East Asia. I have seen Russians with limited English teach English to Chinese. The only qualification for teaching in China is…

https://www.vice.com/en_uk/read/lazy-and-white-go-teach-in-china

And you are disqualified if….

http://www.8asians.com/2007/11/07/chinese-americans-not-american-enough-to-teach-english-in-china/

Many Chinese schools don’t want a professional teacher, but a ‘white face edutainer’ to attract in students, hence the abundance of unqualified, many illegal, ‘English teachers’.

As a teaching professional sent by a home university my work has been undermined by the local staff, much to the frustration of myself and my home university who are attempting to raise standards.

But this is a whole other thread.

If there is a preponderance of unqualified inexperienced ‘English teachers’, the blame must lie with the employers who knowingly employ them, as they have failed to attract and retain good professional teachers.

I am always ambivalent about blogs/books who paint such a stereotypical picture of the ‘bad foreigner’ who is only after easy sex and BS’ing the local Chinese they teach and work with.

This to my mind plays into the more xenophobic attitudes of Chinese guys (particularly) who use the behaviour of the minority of ex-pats as a stick to beat the rest of us, and as an excuse to justify their behaviour and attitudes.

Granted there are those who arrive in China who are “arrogant, lewd and racist”, but certainly not to the extent that is implied by this article. Over my time in China, which has been in a variety of locations, I have only met one guy who could be classed was the ‘over 50’s sexpat’, and found himself quickly isolated and ignored by the local ex-pat community for his disrespectful behaviour (he did not confine his behaviour to Chinese women). Not surprisingly he did not last long in the area by himself as he found he could not survive.

For the most part I found my foreign colleagues and friends polite, respectful and interested in local life and culture.

Whereas if I happen to comment on the lack of respect and offensive comments I have been subjected to by local (male) colleagues, I am labelled as ‘not understanding’ or ‘not trying to assimilate’ and a ‘bad foreigner’.

As I was working in conjunction with a home university there are certain minimum levels of courtesy and behaviour I would expect, regardless of country, as I would give in return.

Life is not, as we know, black and white.

But painting such broad strokes gives a very unrealistic impression of living and working in China, although I can see the necessity for dramatic effect in a work of fiction.

The danger is that too many people see this as the reality of living and working in China.

It is not.

I appreciate your comment, S. One thing I should have mentioned is that Guillard is not the only “bad” foreigner in the book; Daniel definitely has his moments too. The attitudes I noticed among other expats in China arose in my own mind occasionally, so catharsis aside, writing this novel was also an exercise in “exorcising the demon,” I guess you could say. Again, I really didn’t want to come off as judgmental in either this interview or the novel itself, but these types of characters definitely stood out to me during my three years in China, and that’s why I tried to imbue the story with as much ambiguity as possible. The novel has a pretty inconclusive ending, which I did on purpose in the hopes of making the story less black and white, but you are totally right, the contrast between Guillard and Daniel was a huge force in terms of moving the narrative forward. I think that UMDC is one of the more honest novels out there about foreigners living in China, but I understand it’s not going to reflect everyone’s experience. It makes me happy to hear that yours was so different!